Perhaps the ancients not only saw much that is important to us today, but also knew much that we, in the meantime, have forgotten.

Just outside of Center City, Wissahickon Valley is an incredibly beautiful park with lovely trails, nature features, and a surprisingly deep history. One of my favorite places in Philly is the Valley Green Inn, which has operated for hundreds of years as a “rest stop” that serves amazing and homely food right by the river (along with great ice cream). But by far the most interesting landmark in the park is the hermit cave, or troll cave, or hobbit hole.

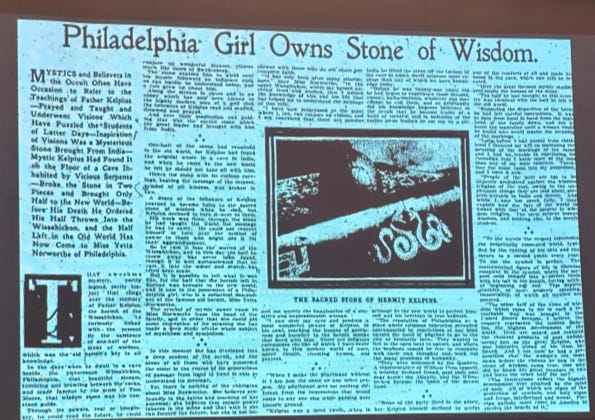

Deep in one of the side trails, there is a small structure built sturdily into the hill. Seen alone, it would be no more than a passing oddity. However, there is a large stone with a curious engraving that made me come back again and again. See for yourself:

What an incredible, juicy find! Over the years, I’d seen and pondered it a handful of times on runs, but never had the time to stew on it. But after a visit last weekend with a friend, I figured I’d better learn more about Mr. Kelpius so that I could at least give a more nuanced explanation to whoever I dragged there next.

Discovering Kelpius

A google search when I got home was, quite strangely in the age of limitless information, unsatisfying at best. Kelpius’s wikipedia page was short and filled with [according to whom?] and [better source needed] qualifications. The other results were dated, sus, or downright garbage — apparent even to my untrained eye.

In general, I learned that he was a German religious mystic and radical that fled to Philadelphia at the dusk of the 17th century. Beyond that, it was really a mystery — was he part of a doomsday cult? An alchemist? Astronomer? Dark Magician that threw the Philosopher’s Stone into Schuylkill River (true)?

It was through a stroke of luck that I found a podcast on Kelpius on Spotify. The guest had authored a book on Kelpius earlier this year, which is, to my knowledge, the only attempt to seriously examine his life, theology, and philosophy. Professor Grieve-Carlson dispelled many of the more silly Kelpian myths but revealed a truth concomitantly strange as his fictions.

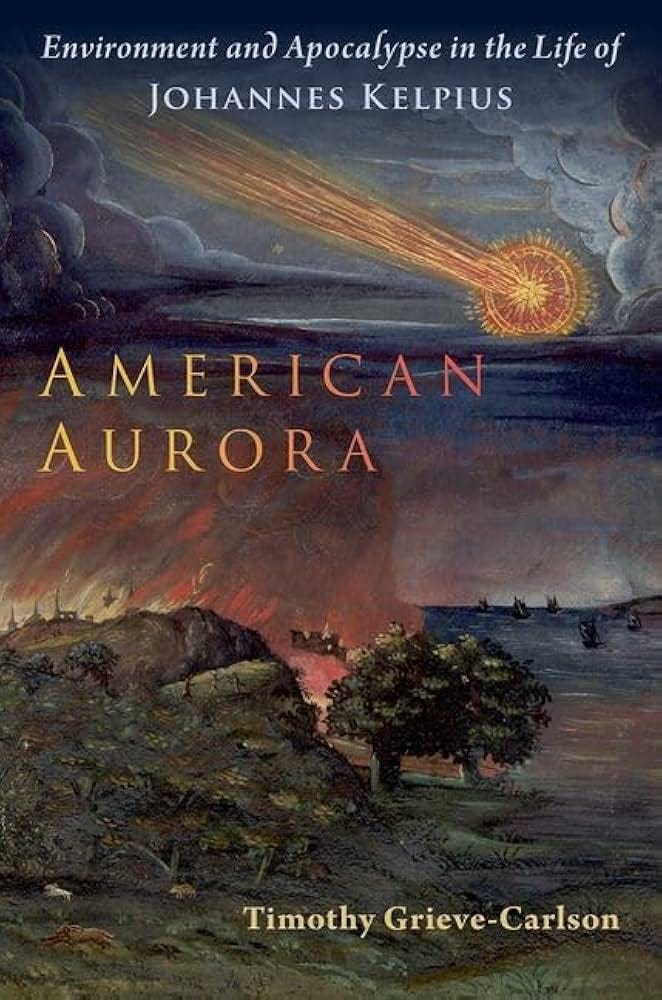

I also started his book, American Aurora: Environment and Apocalypse in the Life of Johannes Kelpius. First off, one of the sickest book titles of all time. It probably slots in at second behind A Prayer for the City, which I just finished reading and will write about in the coming weeks (my newly minted favorite book). The cover is also blazingly epic.

It took me a few days to get through the podcast. At the very end, though, he mentioned that he was coming to Philadelphia for a book talk in November. This was on November 6th. I check his twitter and eerily, flabbergastingly, the event is on November 7th.

I could not help but wonder at the odds that I, in the space of a week: discover Kelpius, discover the first book and podcast about him, and discover the first event about Kelpius probably in decades in my own city on the next day! And how suspicious that Kelpius’s whole belief structure is about finding and interpreting signs from God in the world around us!

Anyways, in a fun side quest, I visited the German Society of Philadelphia’s beautiful library and listened to Prof Grieve-Carlson’s talk, which was incredible.

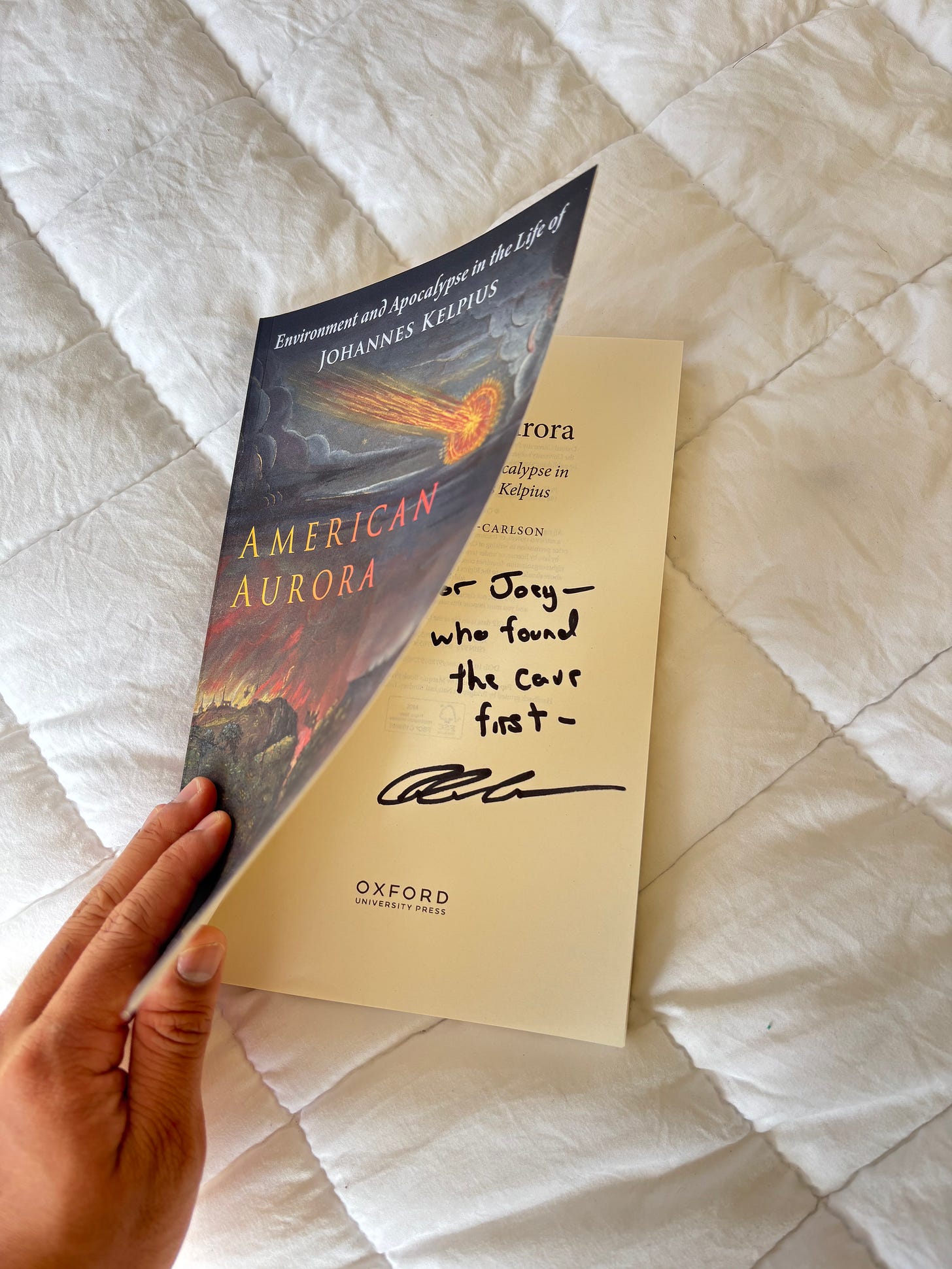

He is a great speaker and really knows his stuff. He also left me an absolutely metal book signing quote —

Kelpian Beliefs

Kelpius lived in a time of great chaos and disorder. Europe was just ravaged by the 30 Year’s War. Various plagues were still circulating. There were large-scale climactic disruptions. Forgotten today, but which left a huge scar on society, was the Little Ice Age, a period of global cooling (2-degree celsius drop!) that led to widespread famine, poverty, and social unrest.

This coincided with increased volcanic activity, which darkened and reddened skies for years, and also the most active comet seasons in recorded history. It seems only natural that these poor people felt that their world was falling apart.

Starting in the fourteenth century, cooling temperatures disrupted our economic and social structures—and may have given rise to the modern world. - New Yorker

There were also changes to regular people’s daily lives, namely a shift in religious practice. This was especially true in Kelpius’s Germany, which was still grappling with the implications of Martin Luther’s Reformation. The author makes a convincing case that, for the average European peasant, Protestantism left a void in their life after the removal of Catholic traditions and beliefs.

Put simply, they had nothing to do! No saints to worship, no music to play, no bread to eat.

Kelpius arose with a branch of radicals known as Pietists. Drawing from Esoteric traditions such as alchemy and Hermeticism, they emphasized a personal relationship with God (sound familiar?) through divinations of signs, miraculous works, and devotional practices.

The students forsake their former way of Learning and applied themselves wholly to Piety and Godliness, leaving and some burning their heathenish Logiks, Rhetoriks, Metaphysiks…

- Kelpius

These mystics would report witnessing “strange things of the Invisible worlds,” including levitation, tears of blood, mind reading, prophecies, and more, much like the miracles from “the days of the Apostles.” We see why he shunned his comfortable academic life in Germany for a life on the run — like all prophets, signs of divinity compelled him to follow a different path.

For Kelpius, the outside world was a reflection of the person — the micro vs macrocosm. Much like how Freud would interpret dreams, Kelpius interpreted waking life, finding meaning in the land, water, and sky surrounding him.

Nothing is Without Voice: God everywhere can hear

Arising from creation His praise and echo clear.

-Johann Scheffler, another Pietist

Life in Philly

Pietists got a little too big for their britches — at one point denouncing the Lutheran Church as the antichrist on Earth — and eventually had to scatter or dilute their message to avoid persecution. Kelpius decided that he would be safe in William Penn’s Philadelphia and came over at the turn of the 17th century.

Once in the States, Kelpius and his followers tried briefly to integrate into Philadelphia society. But they were a little too weird even within a place created for radical acceptance. After a kerfuffle with the Quaker leadership of the city, they retreated into their wilderness compound.

This group of men oddly began calling themselves the Women of the Wilderness, a reference to Revelation 12 —

The woman was given the two wings of a great eagle, so that she might fly to the place prepared for her in the wilderness, where she would be taken care of for a time… out of the serpent’s reach

— and dedicated themselves to worship. They wore rough garments, made songs, and generally minded their own business, but also kept doing cool stuff:

Some have been overwhelmed with extraordinary and supernatural joy, while others have been filled with many tears, testifying that their while hearts seemed to melt in their bodies…

The wilderness “was more of an apocalyptic and esoteric idea than a description of any real geography; wilderness meant hidden, secret.” They were building a relationship with the divine closer to Eleusis than a dry Sunday sacrament.

Takeaways

I am fascinated by mystics, mysteries, and ecstasies. Kelpius scratches all those itches, with the added bonus that I have a fun personal connection to him.

I have written about the Perennial Philosophy, and how religious fringes converge (IMO) into something approaching Universal Truth, in the past. There is something beautiful, and intuitively right, unifying the writings of radical mystics through history — Jesus, Rumi, Dogen, Agrippa, Plotinus, and throw Kelpius in that list.

His influence on Romanticism, Transcendentalism, and general reactions against Enlightenment Rationalism cannot be understated. Kelpius is one of America’s first folk heroes, perhaps sparking our love of nature and wild men and transcendent contemplation / beauty (Thoreau’s Walden immediately comes to mind).

As a side note, figures like Kelpius force me to concede that people have genuinely insane, creative, and revolutionary mystical experiences without the aid of drugs or debilitating mental illness. (Not to say drugs + illness cheapens those experiences — I just think their role in religion and society are too often ignored and minimized.)

These people earnestly lived in a world where people levitated and entered divine ecstasies from sheer willpower. Subjective truth is truth because that’s all we can ever know.

Relatedly, paying homage to one of author Grieve-Carlson’s main theses through American Aurora,

The American Enlightenment would make it difficult for modern readers to clearly understand or interpret the worldview and writings of Kelpius.

The vast majority of humans up until very recently lived within and understood a world entirely alien to us today; a world filled with magic, symbols, mysteries, and touches of divinity.

In Other Words

The author compares two descriptions of comets in Pennsylvania newspapers. The first, in 1769, is accompanied with a commentary:

A comet of pale color appeared… You people, ask yourselves what this star may mean, whether God wants to punish you. O, do penance while there is still time.

The second was a much drier observation in 1829, though the actual event was seemingly of a more fantastical quality:

It arose until it crossed the Delaware… descending with astonishing velocity to the horizon… where it remained ary for a few moments. Suddenly it became exceedingly large and brilliant… [and] soon after became dim and disappeared behind the trees. (seems awful UFO-like to me)

The first was a world, pre-Reason, where things had meaning and deserved interpretation. Within a few years, the world became a place to observe and measure. Kelpius invites us to contemplate on this “vast gulf of knowledge” that separates us from this old world; and whether or not there is anything worth bringing back to the present day.

Philosopher’s Stone

A handful of Kelpius’ followers wanted to inherit the stone upon his death, but he feared that people would use the powerful stone for evil, so he had it thrown into the Wissahickon river.

https://www.buriedsecretspodcast.com/the-philosophers-stone-in-philadelphia/

- J3, the newest member of the Kelpius Society, woohoo! Now numbering a strong 3!